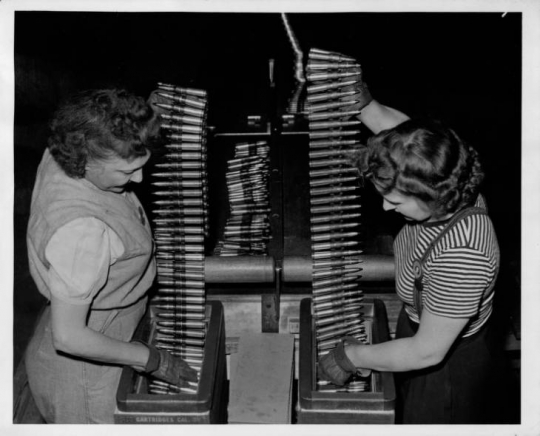

If the Rice Creek could speak, it would tell you stories of the past and future. It would talk of the families who camped along its shores in fall, filled baskets with manoomin, and slept in the shade of towering oak trees. It would speak of the Frenchmen paddling canoes filled with furs. How they traveled between the Mississippi and Mille Lacs, sang songs with gusto, and traded beaver pelts for beads. It might tell you about the wars in countries far away – Germany, Japan, Korean and Vietnam – and the people who came to work day after day, operating machinery that made bullets for the cause.

The future is unwritten, but perhaps more hopeful now – a quiet spot to fish, tall grasses that wave in the wind, and children that giggle as they ride past on bikes, carrying stories around the bend.

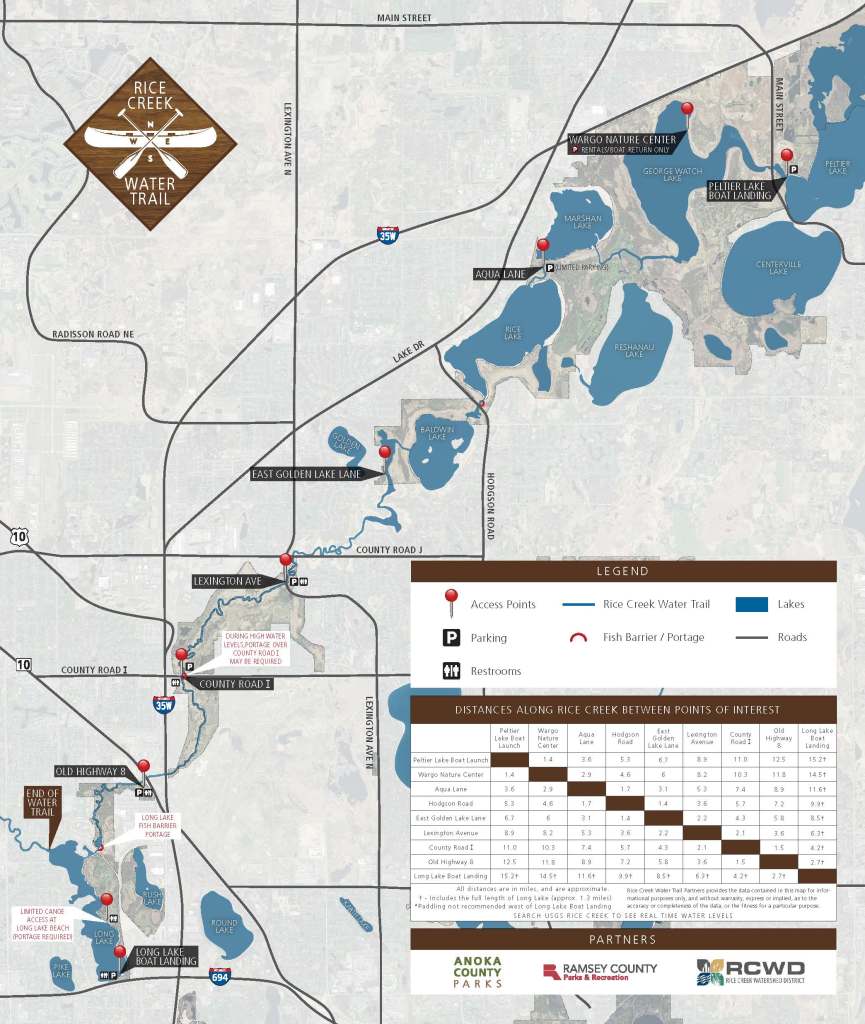

Rice Creek flows 28 miles from Clear Lake in the City of Forest Lake to the Mississippi River, winding past Wargo Nature Center and through the Rice Creek Chain of Lakes until it finally meets the Mississippi at Manomin Park in Fridley. Known in Dakota as Psiŋta wakpadaŋ, meaning “Wild Rice Rivulet,” and in Ojibwe as Panoominikaan-ziibi, meaning “river full of wild rice,” it would be easy to deduce that the creek is named for the wild rice grasses that once grew plentifully in the stream and surrounding wetlands. Ironically or coincidentally, however, it is actually named after Henry Mower Rice, a English-American man from Vermont, who helped to negotiate many of the U.S. and Ojibwe treaties when Minnesota became a state, served as a U.S. Senator, and later acquired much of the land along the lower Rice Creek.

Sometime prior to 1930, portions of Rice Creek were straightened to make way for hay fields and pasture. Later, during World War II, the U.S. Army built its Twin Cities Army Ammunition Plant (TCAAP) on the border of Arden Hills and New Brighton near a section known as the Middle Rice Creek. Workers at the TCAAP produced bullets used in WWII, the Korean War, and the Vietnam War. By 1983, the soil and water surrounding the plant was contaminated with toxic chemicals and the location was designated as a Superfund site. When the TCAAP finally closed in 2005, it created an opportunity for Ramsey County to restore the surrounding landscape and for Rice Creek Watershed District to nurse the neglected stream back to good health.

Today, if you ride a bike along the Rice Creek North Regional Trail, you can enjoy restored oak savanna filled with prairie sage, goldenrod, milkweed, aster and wild rose. The stream has been “un-straightened” and once again follows a meandering course. Populations of aquatic invertebrates and warm water fish are beginning to rebound and there is less sediment and nutrients flowing downstream to Long Lake (New Brighton) and the Mississippi River. Thanks to remediation efforts, the location is no longer considered a Superfund site, and 427 acres of land where the TCAAP once stood are now being re-developed as a mixed-use community with homes, businesses and retail. The U.S. Army will continue to operate the existing groundwater cleanup system for many years to come.

Rice Creek Watershed District received $850K in state funding from the Clean Water, Land, and Legacy Amendment for the Middle Rice Creek restoration effort. In addition, the watershed district leveraged $2.1M in state funding to rehab regional stormwater ponds in St. Anthony and New Brighton to increase flood storage capacity, remove contaminated sediment, and decrease the amount of phosphorus flowing out to Long Lake. The three-part project was completed in 2019 and collectively prevents 107 tons of sediment and 200-300 pounds of phosphorus from washing into Long Lake each year.

If the Rice Creek could speak, it would tell you stories of the people who cared. It would talk about the citizens who lobbied for environmental protections and the government employees who oversaw restoration and remediation efforts. It would talk about the ones who smoothed the soil and planted seeds for black-eyed susans, purple coneflower, and sideoats grama to grow. The future is still unwritten, but perhaps more hopeful now.